"We thought of ourselves as architects:" Coeducation and the Yale Campus, 1968-1973

"Monuments: there are no buildings here"

“The fear and ecstasy of the first beginning

Initiated into the mosaic

Confronting the stony heart of Her

The hollow-eyed old buildings

(Monuments: there are no buildings here

But monuments, each whispering

Coldly never to forget.

I hear them).”

— Richard R. Wilson, 1971 Yale Class Book

Yale’s first women students weren’t alone in finding campus spaces poorly suited to their needs. In a June 1969 letter regarding coeducation, housing, and overcrowding Dean Ernest F. Thompson of Ezra Stiles College wrote that “the temper and stability of the classes… changed with the class of 1970.” The class of 1970 was the first to be admitted by Yale’s new director of undergraduate admissions, R. Inslee Clark, who reshaped the demographics of the student body to (somewhat) better reflect those of the country.

As Yale admitted a more racially and socioeconomically diverse student body, they admitted more students who had spent their teen years in middle class homes rather than boarding school dorms; they admitted more students who were entirely unfamiliar with campus spaces, rather than legacies who had grown up hearing about fathers’ and grandfathers’ antics in Farnam, Commons, Davenport, or Scroll and Key. In short: they admitted students who were often uncomfortable with or skeptical of campus space at Yale. A 1970 survey by the Student Community Housing Corporation found students increasingly using words like "homogenous," "sterile," and "frivilous" to describe Yale's campus. In contrast, they sought "independence" and a more "familial" environment beyond the gates of the residential colleges.

The entry for Calhoun College in the 1972 yearbook intertwines a critique of Calhoun’s architecture with commentary on the social environment of campus and the weaknesses of the residential college system.

In February 1970, a newly-arrived professor described his impression of campus culture and space: “This place reminds me of an elaborate beehive built by a now dead generation which we inhabit and attempt to preserve.” In the following years, more and more undergraduates came to question their role in this “elaborate beehive,” built by generations that resembled them less and less.

This “Disenchantment with the cloistered nature of the residential college” (in the words of the Student Community Housing Corporation), combined with the pressures of coeducation-induced overcrowding, prompted the number of undergraduates living off campus to nearly double, jumping from 5.2% in 1969 to 8.9% in 1970.

Students who moved off-campus often saw themselves as rejecting Yale’s approach to campus space (including its relationship to New Haven), their spatial movements often posed issues for the city as well. Though student occupied-apartments did contribute to the city tax rolls, undergraduates increasingly dominated the best moderately-priced housing units in Yale’s surrounding neighborhoods. As the Student Community Housing Corporation put it in their 1970 report: “[this] acts as a stimulant to white middle class out-migration and as a deterrent to upward housing mobility to formerly low-income residents.”

“Berkeley dining hall—the supposed center of my activity in a university which tried to establish closeness through the residential colleges (or at least so the catalogue said.) Berkeley dining hall, with the intimacy and warmth of the main room of Macbeth’s castle—an exaggeration, perhaps, but it felt that way. People sat at long banquet tables, trying to fill gaps with words.”

— Dori Zaleznik, 1970 Yale Class Book

The Student Community Housing Corporation’s proposed design for row houses on Howe Street — which would mix commercial and residential space, and provide suitable housing for a combination of students, married couples, and families — is indicative of a growing student desire to live in less homogenous, isolated environments.

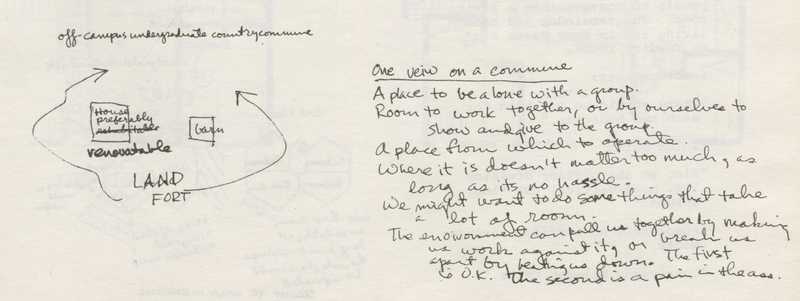

In response to a survey circulated by the Student Community Housing Corporation, one undergraduate turned in a proposal for “country commune” — a house and barn surrounded by a “land fort.” The student describes the possible social implications of living in such an environment: “The environment can pull us together by making us work against it, or break us apart by breaking us down.”