"We thought of ourselves as architects:" Coeducation and the Yale Campus, 1968-1973

"Wondering what lies within the waste"

“The first freshman class to ever have girls in it… The freshmen on the Old Campus that year felt the tear gas wafting over from Chapel Street and the Green…”

— 1972 Yale Class Book

The 1972 Yale Class Book conflates “Nineteen Seventy-Three, Class of” with coeducation and political action in New Haven. Like other students across the country, Yale students of the late 1960s and early 1970s increasingly occupied campus spaces as a means of expressing grievances and exerting political pressure. For a newly coedcuated student body, the shared cause, excitement, and risks of campus protest provided a tentatively uniting force.

Perhaps the most famous politically-motivated occupation of campus space occurred in May 1970, when nine members of the Black Panther Party were put on trial in New Haven for the murder of alleged FBI informant Alex Rackley. When demonstrators converged on downtown New Haven to protest the trial, Yale campus spaces were opened up to provide food, housing, day care services, and gathering spaces. (Visit Kathryn Schemechel's online exhibition "FREE THE NEW HAVEN PANTHERS": The New Haven Nine, Yale, and the May Day 1970 Protests That Brought Them Together," for more on the subject).

In the 1972 Yale Class Book, Pedro Geraldino recounted the story of the May 1970 protests through photographs of gargoyles around Yale’s campus:

Also well-known was the Moratorium to End the War In Vietnam, which took place nationwide in the fall of 1969. Yale students joined in these protests, occupying spaces around campus and New Haven to amplify their message.

“It was a year when, educationally, New Haven’s public green often rivaled the Old Campus.”

— Voiceover from “Coeducation: the Year They Liberated Yale”

The Wright Hall Incident

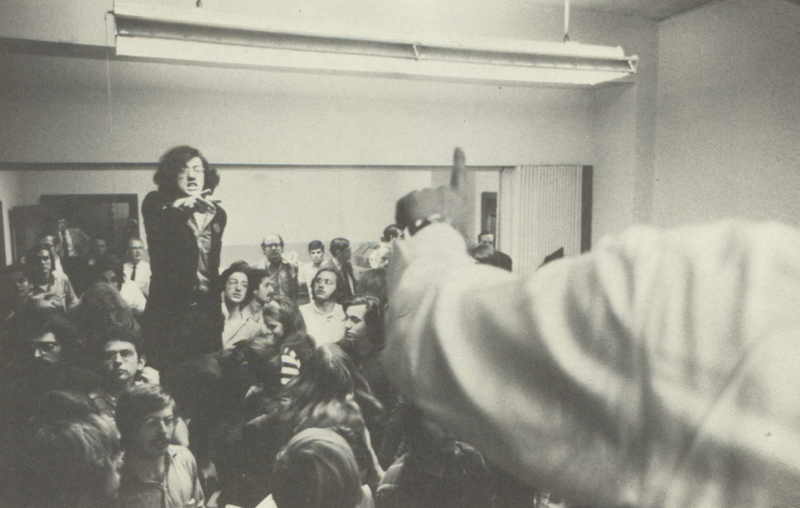

Less well known is the "Wright Hall incident," which occurred during Yale's first coeducational semester, and pulled men and women undergraduates together around issues related to worker's rights, race, occupation of campus space, and University discipline.

In fall of 1969, Yale’s campus erupted in controversy after Colia Williams, a black waitress in Jonathan Edwards College, was fired following an argument with a student worker in the dining hall. Because Williams was a recent hire, she was not yet under the protection of the union, and thus could be fired immediately.

In the days that followed, word of the firing spread. Undergraduates, especially those associated with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), began gathering to discuss the issue. On the afternoon of November third, SDS students met in the Jonathan Edwards College common room.

Interviewer: Are you going to try to actively recruit girls into SDS?

Student: We’re actively recruiting everybody into SDS.

— From “Coeducation: The Year They Liberated Yale”

Shortly after, the SDS students decided to take the issue to the offices of University Business Manager John Embersits, Dining Halls Director Albert Dobie, and Personnel Manager Henry Kremski, located in the basement of Wright Hall, on Old Campus.

The students managed to break past University police in the Wright Hall basement and reach the administrators’ offices. When confronted by the students, Embersits requested a day to assemble the facts of Williams’ case.

To the students, Embersits’ request “appeared… a stalling move” (according to a statement later made by the protestors). They then decided to continue occupying the Wright Hall basement and “hold Embersits and Dobie in the room until a decision had been reached.”

A statement later released by SDS on the Wright Hall incident argued that the injustice suffered by Mrs. Williams extended beyond her firing. As a result of coeducation, the statement argued, dining hall workers faced “speed-up” as they were forced to work faster to serve more students, while still being paid unfair wages. Yale administrators denied this, saying that additional dining staff had been hired for the fall of 1969.

“Black and women workers are disproportionately stuck in the worst jobs at Yale, as everywhere else in the United States.”

— Statement released by 43 of the 47 students suspended following the Wright Hall incident

After several more hours of arguing between administrators and students, University Provost Charles Taylor entered the Wright Hall basement, and at 5:15 pm, told the students that if they did not leave before 5:35, they would face suspension. At 5:51, Taylor announced to the remaining students that they were suspended.

The 47 students who refused to leave Wright Hall basement faced hearings with the Executive Committee, which determined that they should be suspended for one academic year, and vacate campus immediately. Though the sentences were later commuted, the Wright Hall incident cast a long shadow: the first moment when a significant number of men and women undergraduates together faced University discipline for occupation of campus space.

In its final stanza, a poem from the 1971 class book reflects on the early years of coeducation as a turbulent transition, an era of stilted gender relations on campus. But the author also identifies a turning point in these relations: the moment when “They join us in looking at the snow / And wondering what lies within the waste.” For Richard R. Wilson, a skepticism of campus space as it stands, and a tentative, imaginative optimism about how it might be reshaped, marks the initiation of women into the fold of Yale undergraduate culture:

“The women: part-time people to us

Now

We try a gentler hand

And find a sometime hand as answer.

We mold now, now as self-proclaimed,

And that is another beginning.

They join us in looking at the snow

And wondering what lies within the waste.

It is important because they will remember it.”

— Richard R. Wilson, 1971 Yale Class Book

In the 1970 Yale Class Book, the poem “Lines Written on a Sunday” by Maryellen Toman (class of 1972) provides another perspective on the relationship between campus critique and sense of belonging. Toman’s narrator carves out a temporary “temple” for herself on campus through solitary, critical reflection on the world around her.

“People come and go, soothed by my indifference.

They touch me not; for awhile I stand on holy ground,

sip tea and make small decisions

savoring the golden drops of lucidity...

Separately musing on one who will come...

transforming my temple to twilight ruins.

Till then I delight in customs that nourish

Brief, ill-fated civilizations.”

— Maryellen Toman, 1970 Yale Class Book