Graduates (1940s - 1950s)

The 1940s and to the early 1960s were an era of defined gender roles for middle class women. This was the heyday of medical wives’ organizations, both for wives of medical faculty and for wives of medical students. These organizations were intended for socializing and for training women to become good wives of doctors. In Yale directories, women medical alumnae were listed by their husbands’ names with their own names in parentheses. Medical students, still overwhelmingly men, married early. The few women in each class often married classmates or other physicians. They generally followed their husbands to advance their husband’s career. There were no provisions yet for dual residencies, child care, or negotiations for couples to change jobs. Federal granting agencies, which became of major importance to academic medical careers from the 1950s on, offered few awards to women. Residencies in some specialties were difficult for women to obtain. And although some specialty societies like the American Pediatric Society elected women to membership, others did not. The American Gynecological Society admitted one woman in 1921 and the next in 1971. Despite the handicaps, Yale women medical graduates continued to practice in their own fields of medicine, and some excelled.

The 1940s saw the enrollment of the first black women as medical students. There had been African Americans at Yale School of Medicine graduating from 1857 to 1903. However, once the medical school joined with the hospital so that Yale students interacted with hospital patients in clinical clerkships, it became the unwritten policy not to accept black students. This prejudice was finally broken by the admission of Beatrix McCleary in 1944, followed by Yvette Fay Francis in 1946, and Doris Wethers in 1948.

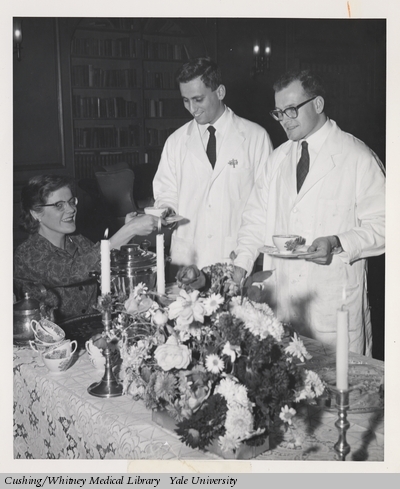

Wives' organizations and student teas

In this 1950s photograph, Mrs. McCollum, a faculty wife, serves tea to medical students at a Student Tea in Sterling Hall of Medicine. Faculty wives, led by Helen Forbes (Mrs. Thomas Forbes) took shifts serving afternoon tea. The faculty wives served as a sponsor for the Medical Dames or Medical Wives, an organization for wives of medical students founded in the early 1950s.

Class of 1948. Beatrix McCleary Hamburg

In 1944, Beatrix (Betty) McCleary became the first African American woman to be admitted to Yale School of Medicine. She was one of three women in the Class of 1948 (the center woman in the photograph), and the first African American to graduate since 1903. Her father, who died young, had been a doctor. Early in her life she knew she wanted to become a physician and especially a psychiatrist. Her community in Harlem supported her ambition. She was the first self-identified African American to attend Vassar College where she was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. Her admission to Yale was a deliberate choice on the part of the Yale medical administration to gradually open the school to black applicants. After medical school, McCleary did an internship and residency at Grace-New Haven Hospital and the Yale Psychiatric Institute. At Yale, she met and married Dr. David A. Hamburg, a resident in psychiatry, with whom she often collaborated. Her research focused on behavioral and developmental issues among adolescents, especially minorities. She developed conflict-resolution programs to manage violence and bullying in schools. Her first academic appointment, as research associate at Stanford, came in 1961 while she was raising her two children. She rose to Chief of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at Stanford from 1974 to 1976. From 1983 to 1992, she was Professor of Psychiatry and Pediatrics at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and then served as President of the William T. Grant Foundation from 1992 to 1998. She was elected to the National Academy of Medicine, and jointly with her husband received the Academy’s 2007 Sarnat Prize for outstanding achievement in improving mental health.

Yvette Fay Francis-McBarnette, Class of 1950

Yvette Fay Francis was the second African-American woman to be admitted to Yale School of Medicine. Born in Jamaica and raised in Harlem, she graduated from Hunter College majoring in chemistry and physics, and received an M.A. in chemistry from Columbia. Early in career, she turned to problems of sickle cell disease, the most prevalent genetic disease affecting the African American community. Her medical thesis studied the biochemistry of an amino acid that was later connected to the genetics of sickle cell. Francis interned at Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago as the first African American intern. She entered private practice in Queens with affiliation to Jamaica Hospital where in 1966, she developed and directed a comprehensive sickle cell treatment program. She married a New York educator, Olvin McBarnette, and raised 6 children, but kept her maiden name for professional purposes. She and her former classmate, Dr. Doris Wethers (YSM 1952), the third African American woman to graduate from Yale, worked together to raise funds for sickle cell disease research.

Page of Catalogue of the Officers and Graduates of Yale University, 1925-1954 (1955)

Even medical students were listed by their husbands’ names with their own names in parentheses. In the earlier catalogue published in 1924, women were listed under their own names with their husband’s surname, and the “Mrs. husband’s name” was in parenthesis.

Women in the Class of 1946m

The subsection looks at the careers of Yale Medical graduates from a class in the 1940s and a class in the 1950s based primarily on what they wrote for their Yale alumni reunions. 1946m was a wartime class that graduated in March 1946.

Margaret (Molly) Johnson Albrink married while in medical school. After internship at Yale, she took time off for the first of three children and an M.P.H. degree in 1951. With the mentorship of John P. Peters, she joined the Department of Medicine at Yale. In 1958, she announced the discovery that serum triglyceride was a more important risk factor for coronary heart disease than serum cholesterol. Her rank at Yale was rose from Research assistant to Assistant Professor. In 1961, she followed her husband, a pathologist, to West Virginia, and continued her research on triglycerides. She received a special recognition award from the American Heart Association.

Ruth Kempe remained in New Haven for three years’ post-graduate training in pediatrics. She married a fellow resident, Henry Kempe, whom she followed to University of California San Francisco. They had five children. Later they moved to Denver. She took a residency in child psychiatry, spent time in private practice, and eventually worked full time in clinical research on child abuse.

Laura Ruth White married classmate John F. Neville, Jr. while in medical school and had five children. She interned in pediatrics at Bellevue Hospital and practiced for a few years while her husband’s career was still unsettled. She then took time off to raise her five children. Later after her husband accepted a position at the Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse, New York, she returned to private practice in pediatrics and psychiatry, and served on the clinical faculty of Medical Center. She was certified in psychiatry in 1974.

Women in the Class of 1957

There were only three women in this class. Information comes from the 50th reunion book and from online obituaries.

Jane Donohue married fellow Yale medical student Frederick C. Battaglia. They went on together to pediatric residencies at Johns Hopkins. She received further training in anesthesiology from Yale. While her husband was a faculty member in pediatrics at Johns Hopkins, she was a member of the anesthesiology department. In 1965, she followed him to University of Colorado School of Medicine. She practiced pediatric anesthesiology at the Children’s Hospital in Denver and was Associate Clinical Professor of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics. While raising her two children, she accompanied her husband on various sabbaticals, and gave lectures in several languages.

Elizabeth Held married Ben R. Forsyth, a resident at Yale. He became a professor of medicine and administrator at the University of Vermont, and in 1990 moved to Arizona State University as a professor of health administration and policy. Elizabeth Held Forsyth raised three children, practiced psychiatry, became best known for over twenty popular books on medicine, often written for children. Some titles are Stress 101, The Disease Book: A Kid’s Guide, and Know about Mental Illness. Many of the books were co-authored by Connecticut science writer, Margaret O. Hyde.

Joyce Daly Gryboski married while in medical school, trained in pediatrics, and held a gastroenterology fellowship under Howard Spiro. She stayed on in the Section of Gastroenterology. She and her husband had three children. She recalled, “Yale was never financially very generous to a working mother but it did provide a laboratory and clinical arena for research which allowed me to publish, write a few books and become recognized as a mother in the field of pediatric GI. In the 70’s I was tenured and wrote one of the first Pediatric GI texts.” She became Clinical Professor of Pediatrics in 1974, and Professor in 1979.