Bawdy Bodies: Satires of Unruly Women

Aging

The vanity and humiliation of older women inspired some of the more cruel productions of graphic satirists, who reveled in portraying aging or generally dissolute female bodies. William Hogarth invented a number of iconic mocking images. In his print Morning (from the The Four Times of Day), an old woman walking through Covent Garden on her way to church foolishly clings to fashion though clearly past her prime. Likewise, the bride in a wintry marriage to a much younger man in Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress, Plate 5 is rendered as ridiculously enthusiastic and lustful despite her decrepit physical condition. The brilliant James Gillray was particularly caustic in his ridicule of older women whose vanity tempted them to extreme but futile attempts to embrace fashionable clothing and recapture youthful beauty. In A Vestal at ’93, Trying on the Cestus of Venus, an old hag at her toilet admires herself in a mirror as putti fit her with the stomach pads that became popular in 1793. Thomas Rowlandson’s Six Stages of Mending a Face, mockingly “dedicated with respect to the Right Honble Lady Archer,” charts the progress of Lady Archer (1741–1801) at different stages of her toilet from nightcap, sagging breasts, and an empty eye socket through extensive cosmetic repairs that deceptively transform her into a pretty, young woman.

Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827)

A Bawd on her Last Legs

Etching and aquatint

Published October 1, 1792 by S.W. Fores

Medical Historical Library, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, Yale University

A fat, unkempt old bawd seated in an armchair thrusts out her bare left leg, revealing a running sore to an aged doctor. The repulsive physical condition of this bawd suggests an equivalency between her diseased body and her moral corruption with imagery recalling Richardson’s description of the death of Mrs. Sinclair, the bawd who conspires in Clarissa’s confinement and rape. The depth of the bawd’s plight is measured against the still youthful beauty of her companion.

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Morning (from the Times of Day), State 2

Engraving on laid paper

Published March 25, 1738

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Hogarth’s scene of Covent Garden in the morning is populated by lower-class urban characters: beggars, market girls, street peddlers, and whores. With a bit of license, the artist juxtaposes Tom King’s Coffee House, a notorious tavern located near Mother Douglas’s brothel, with St. Paul’s Church. At the center of this tawdry scene, a disapproving old woman accompanied by her footboy carrying her Bible walks to church. Hogarth mocks this lady who, though clearly past her prime, clings nonetheless to vanity and fashion.

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

A Rake’s Progress, Plate 5

Etching and engraving

Published June 25, 1735

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

In this moralizing narrative of the wintry marriage of a prodigal rake, Hogarth again cruelly mocks the aging bride. She is portrayed as a rich old lady who foolishly marries a much younger man motivated to wed only by her wealth after he has squandered his own. The evergreens on the altar allude to the perennial lust of the old woman and to a wintry marriage. The decrepit body of the eager bride with pocked forehead and only one good eye is echoed by the dilapidated condition of the church. Both emphasize the moral depravity of the couple.

Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827)

Six Stages of Mending a Face

Etching with hand coloring

Published May 29, 1792 by S.W. Fores

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Rowlandson’s print is mockingly “dedicated with respect to the Right Honble Lady Archer.” The artist’s delight in deriding the vanity of an aging woman, however, matches that of Gillray in A Vestal of ‘93. Rowlandson presents the head and shoulders of Lady Archer at different stages of her toilet, charting the progress from nightcap, sagging breasts, and an empty eye socket through extensive cosmetic repairs that deceptively transform her into a pretty, young woman.

James Gillray (1756–1815)

A Vestal of ’93, State 2

Etching with stipple engraving and aquatint and hand coloring

Published April 29, 1793 by H. Humphrey

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

High fashion did not escape Gillray’s biting humor. He was particularly caustic in his ridicule of older women whose vanity tempted them to extreme but futile attempts to embrace fashionable clothing and recapture youthful beauty. An old hag at her toilet admires herself in a mirror as putti fit her with the stomach pads that became popular in 1793. Allusions to bas-reliefs of classical antiquity in the title and composition add an element of mock dignity to the satire.

The profile of an unidentified old hag of the first state has been re-worked here as an unmistakable portrait of Lady Cecilia Johnston with her conspicuously receding forehead and chin.

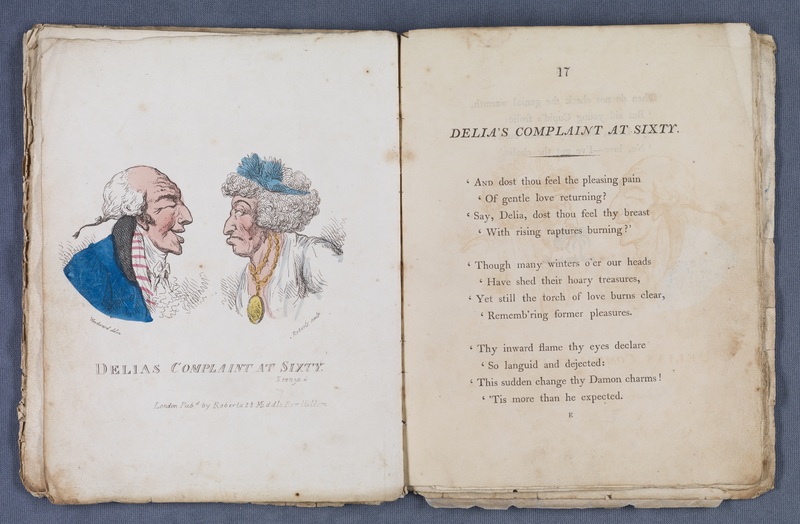

Roberts after George Moutard Woodward (1760–1809)

Delia’s Complaint at Sixty (stanza 4)

Etching with hand coloring

Published by Roberts

In Attempts at Humour, Poetical, and Physiognomical

London: B. Crosby and Co., 1803

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

This modest volume in its original paper wrappers combines versification with caricature sketches of awkward social encounters purportedly reworked from prosaic anecdotes. Here an amorous elderly woman with ungainly features pursues a potential companion. According to the verse, for Delia “still the torch of love burns clear, rememb’ring former pleasures.” Her advances are, however, rejected.

James Gillray (1756–1815)

The Power of Beauty, St. Cecilia charming the brute, or the seduction of the Welch-ambassador

Etching

Published February 1792 by H. Humphrey

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Lady Henrietta Cecilia Johnston (1727–1817) leans forward to kiss the nose of a large goat that climbs into her lap. The lady and the goat are locked in each other’s gaze, dispelling any doubt about the lewdness of the act. For Gillray, Lady Cecilia embodied aged and repulsive coquetry in his relentless ridicule of misplaced vanity among aging society women. An early identification of the goat as William Watkins Wynn has been rejected, so that the Welch ambassador remains unknown.

Henrietta married General James Johnston in 1762. She was notable among fashionable society. She was a friend of Horace Walpole, who referred to her as “the anti-divine Cecilia.”

William Congreve (1670–1729)

The Way of the World

London: John Bell, 1777

The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

In Act 3 of Congreve’s Way of the World (1700), Lady Wishfort and her maid Foible work to repair the cracks and decay of her facial features to match her painted picture in preparation to receive the supposed Sir Rowland—really the servant of Mirabell impersonating an upper-class suitor.

The complex plot of the play revolves around Mirabell’s efforts to win not only the hand of Millamant but also the consent of her aunt and guardian, Lady Wishfort, who controls Millamant’s dowry. Mirabell’s plot to manipulate Lady Wishfort depends on the attribute highlighted by her name: her desire for amorous gratification despite her advancing age. The satiric logic of the play suggests that the self-deceptions of an older woman who absurdly continues to “wish for it” leaves her open to deception and manipulation by others.