iii / Forest and Stream

The disquiet witnessed in On the San Sebastian River, Florida is an indicator of the frustration brewing in Martin Johnson Heade. In 1880, Heade begins to write for Florida publication Forest and Stream under the pseudonym Didymus, through which he expresses his concerns about humans devastating Florida biodiversity.18 The publication encompasses matters regarding ‘Outdoor Recreation and Study,” with a focus on sport hunting, natural history, and conservation.

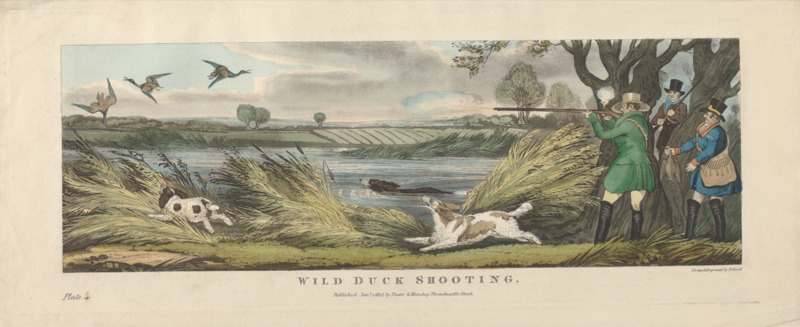

In 1883, Heade publishes “A Decade Wasted!” to mark the ten-year anniversary of Forest and Stream. Rather than applaud the achievements of the publication, Heade instead questions what came from this “herculean effort” other than unregulated “extermination [down] to the last feather...ducks and other aquatic waterfowl oozing away.” 19

Heade himself was an avid game hunter, yet practices with careful moderation unlike many of his colleagues. Heade notes the decline of game over time and mourns the ecological integrity of the wetlands that once existed. His frustration is due to the imbalance of human and nature that he believes stems from moral brittleness. In his 1899 publication “Exterminatory Peregrination,” Heade whistleblows Mr. Shields, professing the man to be a mass murderer. He recounts Mr. Shields romping about Florida’s wilderness, killing “plume birds to rot on the riverbanks, and mutilat[ing] our wild creatures for fun.” 20

Heade’s use of ‘our’ reveals his protective stance against the misuse of human invention, including guns, steamer decks, and notably, the museum. Heade discusses Mr. Shield's inclination to “make a museum out of the outdoors" and turn birds into dead specimens. The narration of his rampage is interrupted by Heade's own interjections, which ask the reader “What ‘museum’ is he in?” before sardonically telling us to “Let [our] ‘museum’ instinct have full play, as it were.”21 His comment is a nod to the collectionsist impulse that drove the exploitation of land and manifested in the carnage of birds and fauna. Countless slaughtered skins were sourced for public and private natural history collections and for commercial millinery purposes coined the Plume Trade. Heade’s ecological reflexivity turns into a physical recoil in the late 1800s, as he witnesses the saltmarsh transform from a nursery into a graveyard.

Heade is reeling from the overconsumption of bird skins, when the Plume Trade becomes widely criticized in the early 20th century and prompts a series of conservation bills and export bans to regulate their exploit.22

| Items from Yale University Collections |