"We thought of ourselves as architects:" Coeducation and the Yale Campus, 1968-1973

"An inscrutable façade of gray"

“Yale University—an inscrutable façade of gray, protected by a unity of architecture and tradition. Who would have been foolish enough to expect to fathom it, to label it, and most of all to adapt to it? But I tried.”

— Dori Zaleznik, 1970 Yale Class Book

The 1972 Yale Class Book describes how “As the petrified freshman reaches New Haven, the first Yale building to swallow him up is Phelps.” In the fall of 1969, Phelps Gate, the main entrance to Yale’s Old Campus, swallowed up first-year women alongside men for the first time (while the less-infamous gates of the individual twelve residential colleges swallowed women transferring into the sophomore and junior classes). Venturing out from dormitories, the women students found a landscape of fraternity houses, secret society tombs, seemingly-impossible-to-locate women’s bathrooms, and a scattered population of women. The daubs of fresh paint and atmosphere of anticipation couldn’t hide the fact that the spatial environment of campus was defined by a 250-year all-male history.

Some women did find supportive female friendships in Vanderbilt Hall or their all-women's entryways in the residential colleges, as administrators had hoped. Still, many others found Vanderbilt to be like a "fishbowl" and the all-women's entryways isolating and lonely. Men and women alike often reported that physical separation led to more stilted gender-dynamics on campus.

First Impressions

On this 1969 campus map, “University Buildings,” like libraries and dorms, are labelled alongside “Affiliated Buildings,” like senior societies and fraternities (the latter were distinguished by a slightly-lighter shade of Yale Blue). The first women at Yale encountered maps like this one upon their arrival, and faced a swath of all-male spaces which the university accepted as an all-but-formal extension of campus.

Hesitant to condone free mixing of men and women, the administration instituted parietal rules for the fall of 1969. These regulations were only remotely enforceable in Vanderbilt Hall, where a 24 hour guard was stationed. Still, in Vanderbilt Hall and the residential colleges alike, students regularly disobeyed the parietal rules without much difficulty.

In a September 1969 letter, Virginia M. Stuermer, M.D. described the hastily-renovated gynecological facilities at the Department of University Health as “woefully inadequate and totally unequipped.” Among other things, the gynecology suite lacked a women’s bathroom.

Dr. Stuermer wrote that: “As a Yale faculty member I am disappointed at the lack of planning for health services for women. As a physician I am stunned at being asked to function at a level far below my capacities because of the lack of equipment. As a woman I am appalled at the cavalier attitude toward the women students.”

In the fall of 1970, a brief exchange between a sophomore student and Elga Wasserman on the subject of mirrors exemplified the recurring question of whether women’s physical accommodations on campus should be identical to men’s, or tailored to their “unique needs.” The question of what these “unique needs” were added another layer to the debate. Wasserman assured the student that the installation of mirrors was “in no sense designed to be a subtle cue, but were rather a response to a widely expressed need. This September, when the mirrors were not installed, I received numerous telephone calls expressing dismay at the absence of mirrors.”

The undergraduate census from September 1970 reveals how an already-small population of women in Yale College was fragmented across various dormitories and residential colleges. The number of women in a given year at a given location hovered in the teens and single digits: there were eleven junior women living in Jonathan Edwards College, nine sophomore women living in Morse College, four junior women living in the Pierson College annex.

“The first women at Yale were geographically separated in their living situations and this dispersion contributed to our sense of resignation to the role of social butterfly. I could walk for blocks at night without seeing another woman's face.”

— Lisa Getman, "From Contestoga to Career"

The 1972 Class Book, written in dictionary format, similarly depicts Vanderbilt Hall as a site of romance or heartbreak for Yale men.

Student Responses: The 1969 Housing Survey

“The women in JE feel that a separate entryway has made us too isolated… We object to the lock on our front door.” JE f

“You might consider just scattering women — period — without worrying about floors.” BK f

“The segregated entryway system has to go.” BK m

“With the girls in separate entryways it has almost seemed like they aren’t even around except at meals. I don’t think this is what coeducation should be like.” SY m

“There should be, in my opinion, no separation w/r/to sex.” PC m

“I think that housing can have a great effect on how well women fit into the University. As long as they are kept locked in a separate entry, it is going to be difficult for everyone to relate as people and not as men and coeds.” BR f

— Responses to the December 1969 housing survey

“Please, please, please reconsider before adding more people to each college. I feel claustrophobic; we all do. We’ve all been close to tears about it at some point or another this year. I should think that Yale would prefer to have quality over quantity in the states of minds of its students, and certainly stuffing 2 people into a garret, made to accommodate one only, is not conductive [sic] to healthy mental welfare… Not only rats become neurotic when overcrowded. Please don’t do this to us; any more will be intolerable.” TD f

— Response to the December 1969 housing survey

In responses to the 1969 housing survey survey, two students advocated for designated entryways for black students and criticized the lack of black women in Silliman College.

“Most men that I know are totally unaffected by coeducation; to them, it’s still the same old male Yale… I feel as if I’m entering some sort of sanctum sanctorium [sic] when I go into the girls’ entryway. Having only a few girls on the floor above or beneath you would be a much more healthy and natural scene.” TD m

— Response to the December 1969 housing survey

The Cross Campus Library

“Many of the girls stated that Yale had no place in which people could meet informally - a possible cause of the feeling that in the event that one didn’t have a date, the only place to go is the library.”

— Women’s Advisory Meeting summary, February 1971

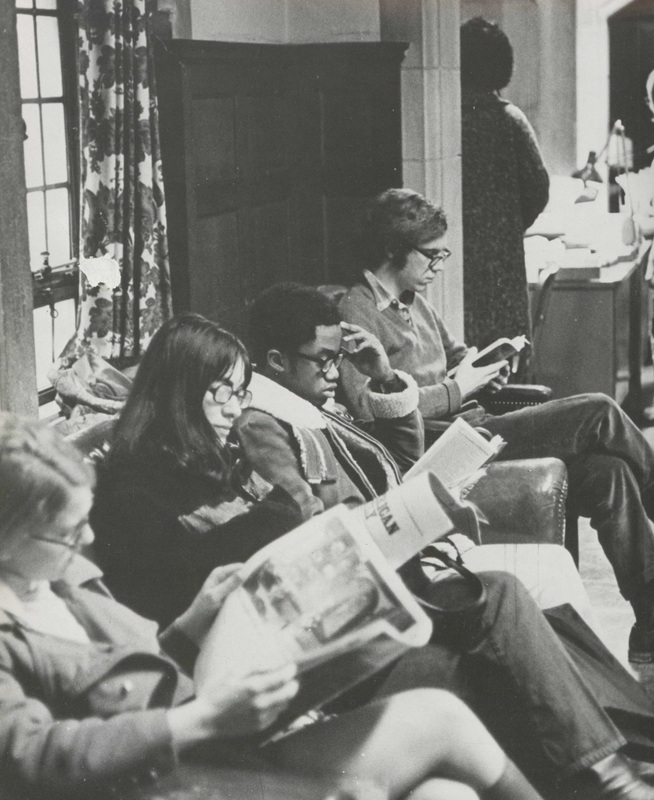

The lack of extracurricular and social spaces available to women, combined with crowded conditions in the dorms, drove many female students to academic spaces. As Lisa Getman recalled, this led to, “Generalization about our psyches… the girls are too serious, the girls are always in the library.” This skew towards academic spaces was not helped by the fact that one of the only facilities to expand alongside the increase in enrollment was the library.

“As you descend into the library through the slick, airport-architecture courtyards, there is a great feeling of lightness which almost succeeds in making you feel pleasant. But after hugging your books to your body so you can get through the inexplicably long and narrow double doors… you confront one of the deadest spaces on the campus, the great beige continuum. The walls are beige; the floors are noiselessly tufted beige; the acoustical tiling is beige; even the light fixtures are mirrored. And what do they mirror? Beige.”

— Richard Brettell, in a February 1971 issue of The New Journal

“The most important criticism of the Cross Campus Library which I have to offer is that it displays a student world which is almost nihilistic, a world which denies the life of ideas and the force of interaction which a library means... It is a little sterile world, cut off in almost every way from the world around it, participating in a contextless style of education” — Richard Brettell, in a February 1971 issue of The New Journal

“Sterling is so dark, and dank, and dreary. It’s like a depressing old church. Cross Campus is brighter and warmer.” — Eliza London, in a February 1971 Yale Daily News article

“It’s like a scrubbed hospital -- sterile and barren and nauseating.” — a first-year woman, in a February 1971 Yale Daily News article

“Perhaps, just maybe, you might meet someone who you’ve been looking for ever since you got here in one of the booths for two. But, then again, it would be hard to start a conversation, because everyone could hear you and it would be hard to really do anything because all your anonymous listeners would come and stare at you through those long narrow windows.”

— Richard Brettell, in a February 1971 issue of The New Journal