"We thought of ourselves as architects:" Coeducation and the Yale Campus, 1968-1973

"Yale generously provided"

“Mother Yale, unlike her usual self, began acting the role of a nervous, excited new father. We lived in Gothic splendor, amidst furnishings of dark leather and mahogany, surrounded by massive towers, empty moats, and a community of four thousand male leaders. We were well protected; Yale generously provided us with twenty credits, new curtains and seven-foot beds, mirrors five inches too high, sex manuals, and security locks which jammed.”

— Alice Young, 1971 Yale Class Book

In the winter of 1969, the Planning Committee on Coeducation finally came to the conclusion that “Yale life centers to such a large extent around the residential colleges that if girls are to be truly integrated into the Yale community this integration has to take place through the colleges.” The maximum degree of gender-integrated housing that Yale had considered thus far would prevail: first-year women would be housed in Vanderbilt Hall on Old Campus (traditionally the home of all first-year students), but sophomore, junior, and senior women would be housed across all twelve residential colleges.

From the time that this decision was finalized, well under a year remained in which to prepare campus for its first women undergraduates. And on an undergraduate campus entirely unaccustomed to women, even seemingly-straightforward renovations, like repainting the bathrooms in Vanderbilt Hall a lively red, took on an air of frenzy and confusion: a rumor spread that the paint color had been chosen because it made women’s complexions look better in the morning.

Vanderbilt Hall: Preparations

Additional security measures — glass and accommodations for a guard — were added at the entrance of Vanderbilt Hall. The transformation of the Vanderbilt entryway is indicative of a growing security presence on campus through the 1970s, as well as the belief, exemplified by Sam Chauncey, that women needed to be protected “more from local undesirables than from Yalies.”

In the spring and summer of 1969, Yale administrators and facilities staff scrambled to anticipate and implement the needs of women students. This memo on renovations for Vanderbilt Hall is marked up with several “No’s,” indicating the tight financial and temporal constraints on the preparations for coeducation.

Proposed renovations for Vanderbilt Hall originally included an “apartment for a young married couple.” Perhaps this proposal was an acknowledgement of the additional support that the first women on a male campus might need. Perhaps it was a vestige of the not-long-gone era in which universities asserted a parental role, especially over female students. Either way, the plan was eventually scrapped due to spatial constraints.

Ezra Stiles College: Vertical vs. Horizontal

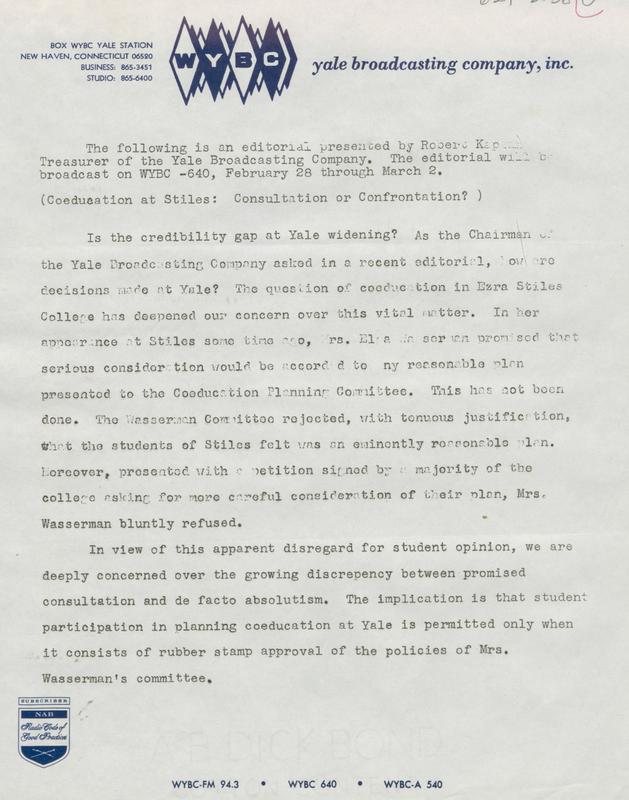

In Ezra Stiles College, tensions around university governance and “equal” and “equitable” treatment of women manifested through a spatial debate: “vertical” versus “horizontal.” Across the colleges, the administration favored “vertical” clustering of women’s rooms.

This arrangement, administrators argued, would take into account women’s unique status as a minority on campus, and encourage community-building between them. This arrangement also allowed for security to be added specifically on women’s entryways, and, at least nominally, it was a stand against completely gender-integrated housing — an uncomfortable prospect that had plagued administrators since the failure of the Yale-Vassar merger. Finally, "vertical" clustering was consistent with the design of Yale's "entryway" system, in which rooms on various floors are connected by a shared stairwell, rather than rooms on the same floor being connected by a shared hallway.

When the administration moved forward with a plan to cluster incoming women “vertically” in several floors of the Ezra Stiles College tower, students immediately pushed back, arguing that the tower would isolate them from the Ezra Stiles community. 125 students ultimately signed the petition in favor of “horizontal” rather than “vertical” clustering of women’s rooms.

Pierson College Annexes: "Anger and Anxiety"

Meanwhile, Pierson, one of the most overcrowded colleges, explored annex housing for male students that would be displaced by women. One possible Pierson annex, an apartment complex at 199-201 Park Street, recently purchased by Yale and managed by the William Hotchkiss company, inflamed tensions around coeducation and Yale’s encroachment on New Haven’s housing stock.

A survey was sent to the residents of 201 Park, surreptitiously asking for the name of their employer. The responses were annotated to indicate whether the tenant could be removed to make room for Pierson students. Yale employees’ questionnaires were marked “No,” non-Yale employees with a check mark, and a tenant supported by state welfare was given a question mark.

“I want to go on record that we were shocked to find that Yale rents out a slum that is shamefully in need of upkeep; that we were deeply embarrassed by the discourtesy of the representative of the William Hotchkiss Company who showed us the house, and who curtly said to tenants as they opened our doors to us, “There are some university people come to look at your rooms,” leaving behind us a swirling wake of anger and anxiety… the students of Pierson would prefer making some sacrifices to humiliating themselves by imposing further humiliation on its tenants.”

— John Hersey, then master of Pierson College, regarding the apartments at 199-201 Park Street

Ultimately, the apartments at 199-201 Park Street were not used as annex housing. But the “swirling wake of anger and anxiety” that John Hersey described would continue to accompany the expansion of Yale’s campus in the coming years.

Silliman College: "Stretched to the Limit"

The letter sent from the Dean of Silliman College to incoming freshman women alludes to the the kind of campus that they would encounter in the fall of 1969: overcrowded, hastily-prepared for coeducation, requiring “good will and good humor” of its occupants.

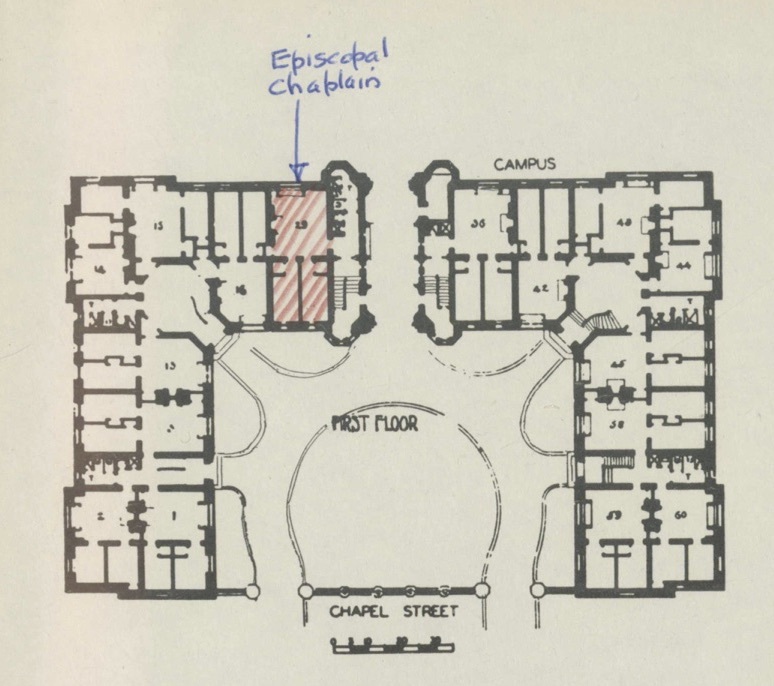

This floorplan for Silliman College shows the sliver of space (entryway N) to be occupied by women in the fall of 1969.