Knight Errant of the Distressed: Horace Walpole and Philanthropy in Eighteenth-Century London

Background on Charity

Both philanthropic organizations based in cities and towns and a plethora of local charities that operated alongside the so-called “old” poor laws dating from the reign of Elizabeth I played a significant role in eighteenth-century Britain. Walpole’s Twickenham possessed two charity schools that were funded by philanthropic bequest. In London, specialist hospitals and asylums catered to abandoned children, women in childbirth, sex workers, and sufferers from venereal disease. The middle decades of the century saw a conscious effort to cut mortality rates and boost the active population during a period of frequent warfare when it was wrongly believed the population was shrinking. Institutions such as the Foundling Hospital became fashionable meeting places where the philanthropically minded could display their compassion and generosity. Walpole liked to give the impression that he eschewed this type of public philanthropy, but given his wealth, social status, and friendships with leading philanthropists, he could not avoid it altogether.

Simon François Ravenet after William Hogarth

The Good Samaritan

Etching and engraving

London: Published by John Boydell, February 24, 1772

Kinnaird 68K(a) Box 320

William Hogarth’s original painting The Good Samaritan (1737) fills a giant canvas on the staircase of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. It depicts the parable from St. Luke’s Gospel (10:30–37) of a Samaritan pouring oil and wine into the wounds of a Jewish traveler, his traditional foe—a favorite emblem of charity (and inspiration for Chatterton’s satire against Walpole). St. Bartholomew’s was founded in 1123 by the Anglo-Norman monk Rahere, who is depicted in the lower-right panel dreaming of the new hospital.

William Hogarth and Luke Sullivan

Moses Brought before Pharaoh’s Daughter

State 4

Etching and engraving

London: Published by William Hogarth, February 5, 1752.

Hogarth 752.02.05.03.4++ Impression 1

William Hogarth donated his painting Moses Brought before Pharaoh’s Daughter (1746) to the Foundling Hospital, where it was displayed in the Court Room. The painting uses the story of Moses’ adoption (Exodus 2:1–10) as an allegory for the Hospital’s work caring for children who had been abandoned. Hogarth’s Egyptian princess is shown in a welcoming posture as she coaxes the clearly anxious foundling, while the child’s birth mother looks on in tears. Hogarth’s paintings for the Foundling were fashionable viewing for eighteenth-century Londoners.

Francesco Bartolozzi after Robert Smirke

Concert Room, King’s Theatre, Haymarket

Etching and engraving

London: Publisher not identified, ca. 1798

Folio 75 B28 804

This ticket to a gala benefit concert held on May 4, 1798, at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket, shows St. Cecilia, patron saint of music, playing the organ while two winged figures look on in rapt admiration. Charity and three children appear underneath, flanked by the lion and unicorn from the royal coat of arms. Benefit concerts were frequent in Walpole’s London and were organized to support good causes or selected individuals deemed worthy of reward. The original ticket, designed by Robert Smirke and engraved by Bartolozzi, was reusable, indicating the frequency of such events.

Parish Removal Order for Jane Symons

England, 1726

File 64 Sh725 T627

Under the 1601 Act for the Relief of the Poor, only people with a legal settlement in a parish were entitled to receive relief there; people without a settlement who relied on welfare could be removed. This removal order, signed by two justices of the peace from the county of Shropshire (“Salop”) and dated March 3, 1726, instructs the church wardens and overseers of the poor in the parish of Lilleshall to remove one Jane Symons to the nearby parish of Shifnal, where she has a right of settlement through her husband: “hereof fail not at your Perils.”

Indenture for the Parish Apprenticeship of Mary Adderley, Aged 9

England, 1769

File 64 St15 769

This indenture for a parish apprenticeship, signed by two justices of the peace, notarized and dated May 9, 1769, binds over a poor girl, Mary Adderley, aged nine, to one John Vernon as an apprentice “in the business of a Housewife” until the age of twenty-one or marriage. The master was to feed, clothe, and instruct his apprentice in exchange for her labor. The lot of parish apprentices was notoriously harsh, and many ran away. The Strawberry Hill Press employed an apprentice (not a parish apprentice) from 1759: one Joseph Forrester, son of a local gardener. (See Thomas Farmer to HW, August 27, 1759, HWC 9:164.)

Account of the Society of Friends of Foreigners in Distress

London: Printed for the Society by W. Marchant, 1814

63 814 So678

Founded after Walpole’s death, the Society of Friends of Foreigners in Distress (motto: “love ye the stranger”) had earlier roots in 1760s Norwich, where Dr. John Murray had established a Society of Universal Goodwill. The Society of Friends’ purpose was to grant relief to foreigners who had no right to relief under the parish system, and to enable such of them as wished to return home to do so. Both the intent and the framing language are typical of the era’s humanitarianism. Walpole counted among his friends the French Protestant refugee Vincent-Louis Dutens (1730–1812), who translated his letters with Lady Ossory.

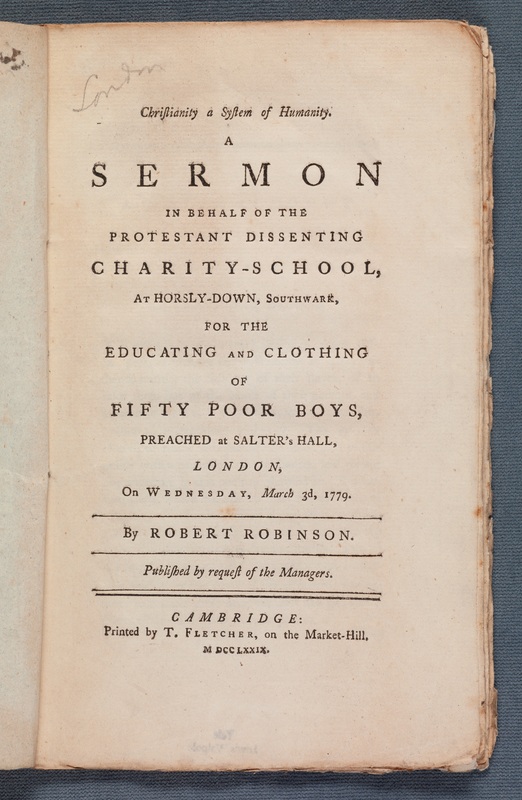

Robert Robinson

Christianity a System of Humanity. A Sermon in Behalf of the Protestant Dissenting Charity-school, at Horsly-Down, Southwark

Cambridge: Printed by T. Fletcher, 1779

68 779 R56

Charity sermons to raise funds for local parish schools were familiar features of Walpole’s Britain and were often published. Robert Robinson (1735–1790) preached this sermon on March 3, 1779, on behalf of the School for Protestant Dissenters in the parish of Horsleydown, Southwark, which educated and clothed fifty poor boys. The children would have been in the congregation and typically sang hymns of gratitude to the donors. In 1791, Walpole (seldom at his warmest with young people) complained of the “croaking and squalling of psalms to a hand-organ by journeymen brewers and charity children” in St. Mary’s Church, Twickenham (HW to Lady Ossory, August 8, 1791, HWC 34:115).

Amock Charity Sermon to a Dissenting Congregation

Etching, hand-colored

London: Published by J. Aitken, May 25, 1795

795.03.25.02+

This print plays on the familiar trope of the charity sermon to mock the royal family. The Prince of Wales and Duke of York appear as “the Poor Charity Children of St James’s Parish” before the “dissenting congregation” of “St Stephen’s Chapel” (i.e., Members of the House of Commons). In the year of publication, the prince’s debts stood at £630,000, and he asked Parliament to pay. In the background Prime Minister William Pitt brandishes the collection plate, while the king and queen escape on horseback saying “charity begins at home.”

James Gillray

Temperance Enjoying a Frugal Meal

Stipple engraving and etching, hand-colored

London: Published by H. Humphrey, July 28, 1792

792.07.28.01+ Impression 1

James Gillray’s engraving satirizes the supposed hypocrisy of George III, who liked to pose as a frugal citizen while living in ostentatious luxury and refusing to settle his son’s debts. The print shows George and Queen Charlotte eating eggs and green leaves from solid gold tableware. On the wall behind the king is an empty frame labeled “The Triumph of Benevolence,” from which hangs a pendant of George as “The Man of Ross,” a reference to the proverbial philanthropist John Kyrle immortalized by Alexander Pope.