Racial Difference in the Yale Medical Curriculum

Learning medicine at Yale before and during the Civil War meant learning about purportedly inherent, biological racial differences that had consequences for understanding differential susceptibility to disease, for diagnosis, and for designing an appropriate therapeutic plan. We know about the place of race in the curriculum from surviving drafts of the lectures that Yale medical professors delivered to their classes, the notes that students took on these lectures, the textbooks that the faculty assigned, and the hand-written medical theses that students were required to write for graduation. What is particularly striking is not only how pervasive scientific racism was in the medical curriculum but just how often it was presented with little elaboration or explanation, suggesting that many of the ideas about the medical meanings of racial difference and the importance of Blackness to medical diagnosis and treatment were seen as self-evident, so widely shared and culturally inbuilt that they did not need special comment. Furthermore, many of the racial medical “facts” taught at Yale and other medical schools in the nineteenth century continue to influence medical practices and treatments today.

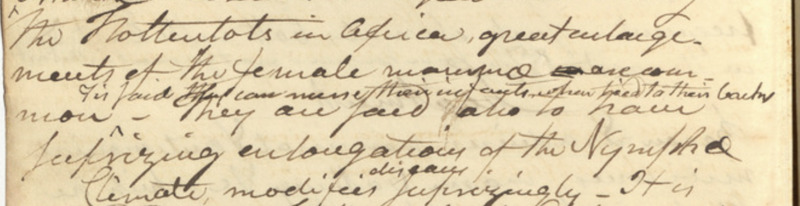

In the 1830s, Yale professor of surgery and obstetrics Thomas Hubbard (Figure 1) routinely paused his lecture on tumors and enlargements of male genitalia to comment on a seemingly unrelated topic. He described for his students “the Hottentots in Africa” as having “great enlargements of the female mammae” (meaning breasts) that allowed them to “nurse their infants when tied to their backs.” He then explained that “they are said also to have surprizing enlongations of the Nymphae [labia minora].” [1] (Figure 2)

Hubbard notes on "Hottentot" sexual characteristics.

Figure 2. Hubbard's notes on "Hottentot" sexual characteristics. "The Hottentots in Africa, great enlargements of the female mammae are common^ Tis said they can nurse their infants when tied to their backs - They are said also to have surprizing enlongations of the Nymphae.” Thomas Hubbard surgery lecture notes (vol. 5), 1830, Box 60, folder 319, p. 234. Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Europeans had been racializing Africans by referencing their supposedly monstrous sexual characteristics since the sixteenth century. [2] The trope of African women having elongated breasts that let them nurse children tied to their backs would have been well-known to Hubbard and his students. Mentioning that rumored trait in a medical lecture, however, also helped to make it a medical fact supported by Hubbard’s authority as a Yale professor. British surgeon Sir Everard Home’s 1823 Lectures on Comparative Anatomy had included similar remarks on a “Mandingo” (West African) woman’s breasts and labia and may have been Hubbard’s inspiration for these remarks, either directly or indirectly. [3] By discussing these traits in professional medical writing and lectures, Home and Hubbard made elongated breasts and labia medically recognized African racial traits, and they described differently racialized people as having medically different bodies.

As jarring as Hubbard’s seemingly out-of-nowhere remark about “Hottentot” breasts and labia might seem to us, they were part of a larger pattern of medical professors, textbooks, and students, reinforcing and furthering common assumptions that bodily, biological differences existed between people of different races and that these biological differences had medical consequences. Histories of ideas about race have traditionally described “scientific racism” as emerging in the 1820s and 1830s, as part of physical anthropology. However, newer studies of race and medicine have revealed that physicians and surgeons were already assuming that race mattered in people’s susceptibility to diseases and in their responses to medical treatment by the 1780s. Physicians and surgeons came to believe that a patient’s race might make them invulnerable to diseases like yellow fever, for example, or that race itself was a pathology leading to behaviors such as dirt eating. [4]

From the late eighteenth century, anthropologists such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach measured human body parts in an effort to establish the differences among races. They particularly lavished their attention on measuring skulls, including the “facial angle” and skulls’ volumes, both of which they supposed related to brain size and thus intelligence. Anthropologists and other scholars also argued about whether the races they perceived were the products of one creation (called “monogenism”) or whether the races were created separately (“polygenism”). Monogenists such as Princeton professor of moral philosophy Samuel Stanhope Smith and British physician James Cowles Prichard opposed polygenists such as Scottish philosopher Henry Home, Lord Kames, and American physician Samuel George Morton. These techniques and arguments informed political debates over slavery and Black citizenship, though whether a particular theorist declared themselves to be a monogenist or polygenist, their shared idea that humans differed according to their race routinely assumed and supported white supremacy. [5]

Medical schools, including the Medical Institution of Yale College, played an active role in disseminating scientific theories about racial differences. Medical students learned about racial theories from lectures and textbooks, and they repeated these ideas in the theses or “inaugural dissertations” that they were required to write to earn their MD degree. Graduates went on to spread these ideas through national and international networks of correspondence and publishing as well as in their medical practices throughout the United States and beyond. [6]

The textbooks that the medical faculty at Yale assigned to their students stressed aspects of anatomy that supposedly defined differences between human races. [7] Polygenist Joseph Leidy’s An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy (Figure 3), for instance, stated that the brain “is the largest in the white race; and, all other circumstances being equal . . . its bulk bears a general relationship with the development of intellect.” [8] Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, and his text was assigned at Yale by anatomy professor Charles Hooker for the 1862-63 session. Leidy also explained that this capacity was related to skull shape, explaining that “the angle of inclination of the fore part of the skull is viewed to determine . . . in some measure to form an estimate of the mental capacity of races and individuals.” [9] Leidy rooted what he posited as white people’s intellectual superiority in the physical body, portraying intellect as a fixed racial trait, and Yale students would have learned these lessons in racial difference as they read about the structures of the human body. His text, like Hubbard’s lectures, also pointed to other anatomical differences between Black and white people that in themselves might seem more benign, such as Leidy’s suggestion that Black people had a peculiar odor due to their physical makeup. “The odiferous glands of the axilla [armpits],” he explained, “are usually much better developed in the negro, in whom the largest reach the size of a small pea,” from which he concluded that “these glands yield a strongly odorous substance, which is somewhat peculiar in the different races.” [10] The overall message, though, was that the races were biologically distinct and that those differences were consequential.

No nineteenth-century Yale faculty members were famed as polygenists like University of Pennsylvania’s Joseph Leidy or Harvard University’s Louis Agassiz. Yet the larger lessons of racial anthropology reached medical students in New Haven through assigned textbooks as well as through lectures. And instruction in racial difference went well beyond anatomy, appearing in lessons on the susceptibility to a range of diseases from tetanus to yellow fever and even chemistry lectures. This pervasive, widespread usage reveals just how common and unquestioned ideas of racial difference were at Yale and in the nineteenth-century United States, more broadly. We know from the surviving notes that Yale medical professors wrote out by hand, and from the notes that some of their students took from their lectures, that Yale professors assumed white bodies to be normal, only pointing out patients’ races when they were not white. They also regularly commented that people of different races were differently susceptible to particular diseases and experienced them with different severity.

Assigned textbooks repeated and added to these lists of race-specific diseases and reactions. In keeping with beliefs about therapeutics that American doctors widely shared, sometimes professors and textbooks recounted how appropriate medical treatment should be varied according to the patient’s race. Textbooks, especially anatomical ones, referenced racial anthropology and measurements to provide a basis in the body for these differing racial illnesses and treatments.

One disease that was commonly associated with the West Indies and thereby slavery and African ancestry was tetanus, or lockjaw. During the new Medical Institution of Yale College’s first year offering courses in the winter of 1813–1814, Nathan Smith, professor of the theory and practice of physic (medicine), surgery, and obstetrics (Figure 4) mentioned in a lecture that lockjaw was “a disease peculiar to warm climates; this disease is not frequent in this climate, but is very frequent in the West Indies.” [11] Smith did not mention race or slavery but implied a connection by citing the West Indies. A few years later, he made the connection explicit, explaining that “the children of the blacks [in the West Indies] have it [lockjaw] from the retention – of the meconium.” [12] “Mecanium,” or “meconium” today, is a baby’s first poop and is usually very dark, thick, and sticky.

In an 1830 lecture, Smith’s colleague Eli Ives (Figure 5) repeated the idea that “retention of the meconium” contributed to “trismuz” (lock jaw) being “very common in the West Indies Islands.” [13] We now know that the bacteria that cause tetanus live in soil and manure, and it often enters the body through puncture wounds. [14] Black West Indians could have been especially vulnerable to tetanus because their owners rarely supplied them with shoes and because the sugar fields where their enslavers forced them to work were regularly fertilized with manure, meaning cuts from the long, sharp sugar cane leaves would have been common and easily infected. [15] Neither Ives nor Smith directly stated that Black West Indians’ race led them to develop tetanus or made them more susceptible to it, but by framing the disease in terms of Black West Indians being more commonly afflicted, they implied race mattered while they overlooked the role that enslaved people’s living and working conditions might have played in differential susceptibility to the disease.

An 1858 textbook assigned to Yale medical students in the 1860s and produced after slavery had ended in the British Caribbean made a more explicit case for the importance of race in susceptibility to tetanus, asserting that “the negro is more disposed to tetanus than the white.” [16] The author of A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine (Figure 6), George Bacon Wood, professor of the theory and practice of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, chose to lump still enslaved Black people with the freed Black West Indians, glossing over any earlier suggestion that place may have mattered as much as race to developing tetanus. Wood went on to claim that “in some situations, while more than one-half of the coloured infants who are born die of the disease, scarcely a white child is attacked.” [17] He also blamed the prevalence of tetanus on “the careless negro population of the South,” where, he claimed, “there is often extreme neglect of proper dressings to the umbilicus.” [18]

Yale medical professors peppered their lectures with reminders about differential vulnerability to other diseases based on race. Nathan Smith, for instance, in one lecture mentioned that scarlet fever “prevails among children [and] generally affects [the] white race more than blacks” and in another cited “a French physician” who believed that typhus was unknown among “Indians,” though whether from lack of exposure, regional health differences, or some innate quality was left unspecified. [19] Similarly, Yale professor Eli Ives told students in his class on the theory and practice of medicine that sometimes typhus “affected the colored people & others [sic] seasons they escape.” [20]

The textbooks that Yale medical students read also conveyed the expectation that a person’s race could protect them from certain diseases while making them more vulnerable to others. Wood’s Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, for example, described inflammation as “more frequent in the black than in the white,” noted that pneumonia was “very common among the black and coloured population of the South,” and explained that in the case of yaws (a skin disease) “children are most susceptible to the contagion; and negroes are said to be more so than whites.” [21] Wood neither supported these brief mentions with evidence nor offered any larger theory of the relationship between race and disease. But like most antebellum American physicians he assumed that such a relationship existed and, by including it in a medical textbook, made it part of accepted medical knowledge. Wood’s textbook also used its description of scrofula [a bacterial infection] to give medical support to the “one-drop rule,” which posited that a person with any Black parentage was also Black, stating without explanation that “the negro, or person of mixed blood between the negro and white, is much more subject to it [scrofula] than the pure white.” [22]

Wood also linked Black health to specific climates, suggesting that people of African descent were naturally unhealthy in the cooler U.S. North. He explained that “Negroes, from their greater susceptibility to cold than the whites, are much more subject to phthisis [tuberculosis] in cold or temperate climates” and that “Negroes are, in this climate [Philadelphia, where he lived], more disposed to the disease [of pulmonary tuberculosis] than the whites.” [23] The association of Black health with warm places such as the U.S. South and Caribbean was commonly used to support slavery and the removal of free people of color from the United States to places like the colony of Liberia in Africa.

In fact, the idea that Black people were innately suited to hotter places pervaded the Medical Institution’s curriculum. In a chemistry lecture on color and the attraction of heat to darker shades—a lecture completely unrelated to anatomy or people—Professor Benjamin Silliman posed the rhetorical question, “Why do Black people endure heat better than cold?” [24] Silliman and his family had been Connecticut slaveholders, and he benefitted financially and professionally from slavery throughout his life despite often expressing antislavery political views. This background helps explain why Silliman believed in racial differences, but his off-handed mention of them in a chemistry lecture reveals that he assumed that students would relate to and readily understand the association of Black people with heat. Silliman understood the belief in race-specific fitness for climates to be widespread.

The idea that Black people were healthier in and therefore better suited to warmer places was also reflected in curricular discussions about “tropical” diseases such as yellow fever and malaria. In the nineteenth century, medical writers often disagreed on the relationship between yellow, remittent, and intermittent fevers, sometimes arguing one type of fever could turn into another under certain conditions and other times arguing that they were distinct. [25] Historians have long pointed out that enslavers used Africans’ supposedly lesser morbidity and mortality in plantation environments to defend slavery, but references to race and slavery do not appear in Yale Medical School notes on these topics. [26] One student, Frederick Treadway from New Haven, wrote his MD thesis on yellow fever (Figure 7) in 1863, in the middle of the Civil War. Treadway summarized contemporary knowledge of yellow fever, writing that “most writers on the subject, agree that in comparison with other races, the negro is least liable to be attacked with the disease. In this country, this exemption is in direct ratio, to the amount of African blood, the more the Caucassian [sic] the greater the liability.” [27]

Treadway’s conclusion is especially striking because the one authority he cites, Philadelphia physician Réne La Roche, moved from not mentioning race in an 1853 article on yellow fever to representing it as a crucial element in a two-volume work published just a few years later in 1855, where he made a robust case for the disease’s differing racial effects. LaRoche’s article argued that yellow fever was caused by local “sources of malarial infections” and was not “transmissible from one individual or place to another,” and the book made the same argument. [28] In the article, La Roche mentioned race only briefly. He cited an instance where “black recruits from the coast of Africa” did not catch yellow fever when the crew of the ship they were on did, which La Roche interpreted as evidence that the “black recruits” did not bring the disease aboard. [29] La Roche also mentioned that a case in which “Europeans, newly arrived in a tropical climate” did catch the fever, but he did not draw any racial conclusions. He highlighted that the sick had only just come to the climate rather than focusing on their race. [30] However, La Roche’s later two-volume tome made an explicit case for the role of race in affecting yellow fever. In a chapter subsection entitled “Race” (Figure 8), La Roche contended that “experience everywhere teaches that the disease [yellow fever], without completely sparing … the individuals of African birth or origin … affects more generally and severely the white race.” [31] Effectively, he argued that both Black and white people could catch yellow fever and that time in cooler and temperate areas made all people more susceptible. La Roche ultimately concluded, however, that “the negro is enabled to enjoy a comparative exemption from fevers of all grades arising from malarial exhalations.” [32] Here La Roche made one of the strongest possible claims of innate racial difference by specifically excluding other potential factors that might have granted people protection from yellow fever. Though there is no way to know for sure, Treadway likely read and regurgitated this second, explicitly racist understanding of yellow fever. Nevertheless, La Roche’s shifting perspective on racial susceptibility to yellow fever illustrates the range of nineteenth-century medical opinions about race.

Treadway would have also learned from another of his assigned textbooks that a person’s race mattered to how affected they were by yellow fever. Wood in his Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, like La Roche in Yellow Fever, explained that “Negroes are certainly much less under the influence of the morbific cause [of yellow fever] than the whites. They are not only less frequently attacked, but are also more mildly affected when attacked. This relative impunity does not extend equally to those of mixed blood, who seem to be susceptible in proportion to their approach to the white.” [33]

Some Yale medical students who wrote their theses about remittent and intermittent fevers associated those fevers with southern heat and repeated the belief that the fevers affected Black people less frequently than white people, much like Treadway did in his thesis on yellow fever. They, too, learned about this supposed connection from textbooks assigned at Yale and from other medical texts they cited in their theses. However, other students, including those from “hot” areas associated with the illnesses, made no mention of race, instead focusing on specific environmental causes and treatments. At least one textbook also failed to mention race when describing “bilious remittent fever.” We cannot know whether these students and the textbook’s author made these choices purposefully, but the fact that they did not connect fevers to race demonstrates that racial difference did not always matter in diagnosing and treating disease. In 1842, Philo Nichols Curtis wrote his thesis on intermittent fever and remarked on its special threat to white Americans. He explained that the fever “demands a careful & attentive investigation by every physician in our country; but more particularly those of our Southern & Western States.” Curtis then justified this judgment by stressing that in “some years there is scarcely a white person escapes an attack of this disease. . . . The white population are more frequently the subjects of this as well as of every other disease peculiar to this section of country.” [34] (Figure 9)

Excerpt from “Dissertation on Intermittent Fever”

Figure 9. Curtis on race and intermittent fever, from his thesis: “Some years there is scarcely a white person escapes an attack of this disease for many miles in extent. The white population are more frequently the subjects of this as well as of every other disease peculiar to this section of country.” Philo Nichols Curtis, “Dissertation on Intermittent Fever,” (1842). Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library, Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library, Yale School of Medicine.

Curtis came to Yale from nearby Newtown, Connecticut, and may not have visited the West or the South before describing the prevalence of fever there. His comments about regional and racial differences reflected the widely held opinion that people of African descent were naturally protected from diseases associated with heat, while white people were not, and the medical reading he did for his thesis could have reinforced this idea. [35] Curiously, the expert on intermittent fevers that Curtis cited, Jean-Louis-Marie Alibert, the personal physician to multiple French kings and founder of French dermatology, stressed climatic causes and did not mention race as protecting anyone. Alibert did contend that the fever “seldom attacks any persons but Europeans who visit the West Indies,” but he did so in the context of suggesting that all “native inhabitants are generally exempt from it.” [36] Alibert’s translator and editor further stressed the climatic aspect, arguing that “the pestilential endemic of the West-Indies spares the natives of those islands, as well as foreigners long accustomed to the climate, and confines itself to persons lately arrived from higher latitudes.” [37] Essentially, Alibert and his translator believed people from Europe were at risk of catching intermittent fever because they were new to a hot place, not because of their race. Curtis’s choice to mention race as a risk factor is all the more striking when his source material did not.

James Austin, James Hyatt Harriott, and Henry Williams Foster all wrote theses on intermittent and remittent fever that did not mention race as an inciting or protecting factor. They did, however, associate the fevers with hot places such as the U.S. South. Even though physicians from such hot climates often stressed the role of personal behavior in determining health in them, Harriott, from Turks, the British West Indies, and Foster, a Black student from Liberia, Africa, repeated the association of fevers with heat. Harriott’s thesis focused on the diagnosis and treatment of fever in individual patients, while Foster’s focused on how the specifics of location and individual behavior contributed to the disease. Austin did not explicitly mention race and, instead, repeatedly and broadly indicted “hot climates” and “heat” in general for acting as a “predisposing … cause.” (Figure 10) [38]

Though Austin also did not discuss race in relationship to remittent fever, two of the physicians whom he cited repeatedly discussed the impact of race while positioning climate and heat as a cause of fever. One mentioned that “negroes … resist[ed] the causes of fevers… [and] suffer[ed] infinitely less than the Europeans” but vacillated between suggesting that this was due to the “habit” of living in the climate and implying that innate differences allowed them “to do whatever duty or hard work was to be done in the heat of the day, from which they do not suffer, though it would be fatal to Europeans.” [39] Another of Austin’s sources remarked that “there are among the negroes many contagious febrile complaints, to which white people are not subject.” [40] This second source further explained “that negroes are not subject to the yellow and some other fevers,” though added that those “who have been in Europe, or the higher latitudes of America, are subject to the yellow fever” and “that people of different shades between white and black are as subject to the fevers of white people as these themselves are.” [41] Austin, like Harriott and Foster, apparently thought that a study of the causes and treatment of remittent and intermittent fevers did not need to reference race.

Hubbard’s reference to “Hottentot” sexual characteristics that began this essay was not the only instance of a professor interlinking discussions of sexual and racial traits. In his first year teaching at Yale, Hubbard’s predecessor as professor of surgery, Nathan Smith, gave an unusual lecture related to sexual desire, sexual activity, and marriage. He explained that “It makes no difference who we cohabit with; I mean the [sexual] pleasures are the same, black or white; but it makes a material difference with whom we marry.” [42] (Figure 11) This juxtaposition seemed to imply that Smith acknowledged interracial sex while condemning interracial marriage. By specifically mentioning interracial sex and reproduction in a medical lecture, Smith used his authority to reinforce the contemporary racial idea that people of African descent were more libidinous and therefore more available for sex outside of the cultural norms of marriage. Both Hubbard and Smith linked non-white people with sexual traits that othered them.

Extract of notes from Nathan Smith’s lecture on sexual pleasure.

Figure 11. Medical student Peter Woodbury’s notes from Nathan Smith’s lecture on sexual pleasure. "It makes no difference who we cohabit with; I mean the pleasures are the same, black or white; but it makes a material difference with whom we marry.” Peter Woodbury notes of Nathan Smith lecture, 1813–1814, box 54, folder 294, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Racial differences ranging from anatomy to disease susceptibility and treatment were assumed to be medically significant. Other professors followed Hubbard in specifically referencing non-white people when discussing sex and genitalia, even while most case studies in their lectures involved white patients. Professors rarely mentioned a patient’s race at all, in fact, but when they did, it was nearly always to mention that the patient was Black. The medical school’s lecturers presumed a normative white body, meaning that they understood people of other races to be deviations from ordinary, presumably healthy whiteness. Like other contemporary physicians, they discussed supposed Black racial differences from whites as departures from the norm without ever describing white racial differences as deviations. [43] The impact of the racial tropes taught at Yale School of Medicine and other medical schools in the nineteenth century remains with us today. In the United States, Black health and longevity statistics lag behind those of whites. Despite an overall decline in infant death rates since slavery, the gulf between Black and white infant death rates has grown, with non-Hispanic Black infants dying at more than twice the rate of non-Hispanic white ones in 2016. Pregnant Black women also continue to die at three to four times the rate of white women in the United States, while physicians and other medical practitioners often minimize or dismiss Black women’s self-reported symptoms, including pain. [44] Medical professors also continue to pass on assumed racial differences to their students, not unlike their nineteenth-century predecessors. A well-known 2016 study of University of Virginia medical students revealed that half of white medical students believed incorrectly that Black people differed biologically from white people. The students repeated tropes about Black people having supposed racial traits such as thicker skin and stronger bones, and the study demonstrated that students who had these beliefs rated Black patients’ pain lower than whites and made worse treatment recommendations. [45] If medical schools, including Yale’s, are to repair the damage done by spreading and reinforcing racist beliefs, they must actively teach their students that perceived racial traits are the product of slavery and white supremacy rather than biological facts.

Endnotes

- Thomas Hubbard surgery lecture notes (vol. 5), 1830, box 60, folder 319, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

- Jennifer L. Morgan, “‘Some Could Suckle over Their Shoulder’: Male Travelers, Female Bodies, and the Gendering of Racial Ideology, 1500-1770,” William and Mary Quarterly 54, no. 1 (1997): 167–92; Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

- Christopher D. E. Willoughby, Masters of Health: Racial Science and Slavery in U.S. Medical Schools (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2022), 56. On the persistent nineteenth-century white fascination with genitalia as a sign of racial difference, see Molly Rogers, Delia’s Tears: Race, Science, and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010), 220–21.

- Rana A. Hogarth, Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780-1840 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017). See also Suman Seth, Difference and Disease: Medicine, Race, and the Eighteenth-Century British Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Willoughby, Masters of Health, 57–62. See also William Ragan Stanton, The Leopard’s Spots: Scientific Attitudes toward Race in America, 1815-59 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960); Nancy Stepan, The Idea of Race in Science: Great Britain, 1800-1960 (Hamden, Conn.: Archon, 1982); Ann Fabian, The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010); and Melissa N. Stein, Measuring Manhood: Race and the Science of Masculinity, 1830–1934 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

- Willoughby, Masters of Health, esp. chap. 4.

- So far, only textbooks mentioned in the Annual Circular of the Medical Institution from the 1861-2 winter session through the 1870-1 winter session have been identified. Christopher D. E. Willoughby notes that by the 1860s anatomists no longer felt the need to prove their arguments of racial difference and instead simply asserted differing racial anatomies, meaning this sample of textbooks comes from this later period and explains why racial differences are mentioned without significant support. See Willoughby, Masters of Health, 97–100.

- Joseph Leidy, An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1861), 514.

- Leidy, An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy, 88.

- Leidy, An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy, 634.

- Peter Woodbury notes of Nathan Smith lectures on the theory and practice of physic, surgery, and midwifery, 1813–1814, box 54, folder 293, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), 206.

- Notes of Nathan Smith lecture on theory and practice of physic, 1819–1820, box 42, folder 229, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), 35.

- Notes of Eli Ives lecture on the diseases of children, 1830, box 42, folder 233, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), 7–8.

- “Tetanus Causes and How It Spreads | CDC,” accessed March 28, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/tetanus/causes/index.html.

- Rebekah Lee, Health, Healing and Illness in African History (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021), 41. A lack of shoes would have also allowed enslaved people to be infected more easily by bites from chiggers, another entry point for the tetanus-causing bacteria, and a lack of access to fresh meat, dairy, fruits, and vegetables likely led to calcium and vitamin D deficiencies which would have further contributed to their greater susceptibility. Kenneth F. Kiple and Virginia Himmelsteib King, Another Dimension to the Black Diaspora: Diet, Disease, and Racism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 75, 100–104, 189; Richard B. Sheridan, Doctors and Slaves: A Medical and Demographic History of Slavery in the British West Indies, 1680-1834 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 238; B. W. Higman, Slave Populations of the British Caribbean, 1807-1834, with a new introduction (1984; Kingston, Jamaica: The Press, University of the West Indies, 1995), 224–25; Leslie Baucum, Ronald W. Rice, and Lester Muralles, “Backyard Sugarcane: SS-AGR-253/SC052, Rev. 10/2009,” EDIS 2009, no. 9 (October 31, 2009): 2, https://doi.org/10.32473/edis-sc052-2009. Justin Roberts has noted an increase in enslaved people’s mortality on Jamaican sugar plantations during the manuring season, but he does not connect this with any specific cause beyond the demanding labor. He also stresses that white mortality did not rise in the same part of the year and concludes this increased mortality was related to the specific conditions of enslaved people’s labor or living conditions. The manure itself could have been the source of additional pathogens, including the bacteria causing tetanus. See Justin Roberts, Slavery and the Enlightenment in the British Atlantic, 1750-1807 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 176–77.

- George Bacon Wood, A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, 5th ed. (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1858), 2:826.

- Wood, A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, 2:824.

- Wood, A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, 2:824n. Curiously, two Yale medical student theses written in the 1850s on tetanus avoided the subject of race altogether and examined local cases, especially on Long Island. This approach to discussing tetanus suggests that the students may have agreed with their professors that the disease was less common among white people but that it still merited local attention. William Orville Ayres, “Dissertation on Tetanus,” Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library (1854), https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3755; David Anson Hedges, “Dissertation on Tetanus,” Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library (1857), https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3787.

- Notes of Nathan Smith lecture on the theory and practice of physic, 1832, box 42, folder 234, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), 161; Notes of Nathan Smith lecture on the theory and practice of physic, 1819–1820, box 42, folder 229, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), 111.

- Levi D. Wilcoxson notes of Eli Ives lecture on the theory and practice of physic, 1840–1841, box 55, folder 298, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), 57.

- Wood, A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, 1:38, 2:18, 2:474.

- Wood, A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, 1:771.

- Wood, A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, 2:88, 1:116.

- John E. Newcomb notes of Benjamin Silliman lecture on chemistry, 1827–1830, box 52, folder 283, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), 5.

- These disagreements can be seen in textbooks assigned and theses written at Yale. See Jean-Louis-Marie Alibert, A Treatise on Malignant Intermittents, trans. Charles Caldwell, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Fry and Kammerer, 1807), iv, 186; Wood, A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, 1:288; Sir Thomas Watson, Lectures on the Principles and Practice of Physic: Delivered at King’s College, London (Blanchard and Lea, 1858), 501, 505–6; James Hyatt Harriott, “Dissertation on Bilious Remittent Fever,” Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library (1859), https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3803.

- A sample of 42 of the 105 sets of lecture notes in the Yale Course Lectures Collection were examined for discussions of race (Yale Course Lectures Collection [RU 159]). Many historians have studied the widely held European and Euro-American belief that “hot” places were healthier for African-descended people than for Europeans and that Black people were often considered immune from specific diseases found in such areas. While earlier studies often worked from the assumption that white enslavers were noticing actual mortality patterns related to people’s places of birth and their exposure to disease rather than race, recent research has argued that enslavers were making a convenient argument in support of slavery without real evidence or even believing their own arguments. Compare Philip D. Curtin, The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780-1850 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964); Philip D. Curtin, Death by Migration: Europe’s Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989); Margaret Humphreys, Yellow Fever and the South, paperback ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999); J. R. McNeill, Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010); Peter McCandless, Slavery, Disease, and Suffering in the Southern Lowcountry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011); Mariola Espinosa, “The Question of Racial Immunity to Yellow Fever in History and Historiography,” Social Science History 38, no. 3 (2014): 437–53; Sean Morey Smith, “Seasoning and Abolition: Humoural Medicine in the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic,” Slavery & Abolition 36, no. 4 (October 2015): 684–703; Urmi Engineer Willoughby, Yellow Fever, Race, and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century New Orleans (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2017); Katherine Johnston, The Nature of Slavery: Environment and Plantation Labor in the Anglo-Atlantic World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022).

- Frederick Treadway, “Dissertation on Yellow Fever,” Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library (1863), https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3857.

- R. La Roche, “Facts and Observations on the Origin of Yellow Fever from Local Sources of Infection, as Illustrated by Occurrences on Board of Ships,” American Journal of the Medical Sciences 50 (April 1853): 316.

- La Roche, “Facts and Observations on Yellow Fever,” 336.

- La Roche, “Facts and Observations on Yellow Fever,” 339.

- R. La Roche, Yellow Fever, Considered in Its Historical, Pathological, Etiological, and Therapeutical Relations: Including a Sketch of the Disease as It Has Occurred in Philadelphia from 1699 to 1854, with an Examination of the Connections between It and the Fevers Known under the Same Name in Other Parts of Temperate, as Well as in Tropical, Regions (Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea, 1855), 2:60.

- La Roche, Yellow Fever, Considered in Its Historical, Pathological, Etiological, and Therapeutical Relations, 2:66.

- Wood, A Treatise on the Practice of Medicine, 1:329.

- Philo Nichols Curtis, “Dissertation on Intermittent Fever,” Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library (1842), https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3571.

- Curtis did practice in North Carolina for perhaps a decade after graduating from Yale. Yale University, Obituary Record of Graduates of Yale University (New Haven, 1905), 1360.

- Alibert, A Treatise on Malignant Intermittents, 186–87.

- Charles Caldwell, “Appendix: An Essay on the Pestilential or Yellow Fever, as It Prevailed in Philadelphia in the Year Eighteen Hundred and Five,” in A Treatise on Malignant Intermittents, ed. Charles Caldwell, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: Fry and Kammerer, 1807), 12.

- James Austin, “Dissertation on Remittent Fever,” Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library (1845), https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3627; Harriott, “Dissertation on Bilious Remittent Fever”; Henry Williams Foster, “Dissertation on Intermittent Fever of West Africa,” Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library (1861), https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/3829.

- John Hunter, Observations on the Diseases of the Army in Jamaica (London: G. Nicol, 1788), 24, 36–37, see also 140, 192–93. Hunter also included a separate chapter on “The Diseases of Negroes” despite acknowledging they “fell seldom under [his] observation” (chap. 8, p. 305).

- Philips Wilson, A Treatise on Febrile Diseases, Including Intermitting, Remitting, and Continued Fevers; Eruptive Fevers; Inflammations; Hemorragies; and the Profluvia;..., 1st American ed., vol. 1 (Hartford, CT: Oliver D. Cooke, 1809), 182.

- Wilson, Treatise on Febrile Diseases, 1:192.

- Peter Woodbury notes of Nathan Smith lecture on the theory and practice of physic, 1813–1814, box 54, folder 294, Yale Course Lectures Collection (RU 159), 219.

- See Leslie A. Schwalm, Medicine, Science, and Making Race in Civil War America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2023), 6.

- Deirdre Cooper Owens and Sharla M. Fett, “Black Maternal and Infant Health: Historical Legacies of Slavery,” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 10 (October 2019): 1343, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305243.

- Kelly M. Hoffman et al., “Racial Bias in Pain Assessment and Treatment Recommendations, and False Beliefs about Biological Differences between Blacks and Whites,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, no. 16 (April 19, 2016): 4296–4301, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113.