Gather Out of Star-Dust: The Harlem Renaissance and The Beinecke Library

Gather Out of Star-Dust: Collecting a Renaissance for the Present and Future

From the anthologies gathered by James Weldon Johnson and Alain Locke, to the folkways captured by Zora Neale Hurston, Sterling Brown, and W. C. Handy, to the legendary library collections founded by Jesse Moorland, Arthur Schomburg, and Carl Van Vechten, the Harlem Renaissance was characterized by the act of collecting. African American cultural production in the aggregate would, according to Johnson, show the world that African Americans were not intellectually inferior. The collected work of writers of this period impressed onlookers enough to name the movement a “Renaissance.”

The Harlem Renaissance remains one of the most studied periods in American history; this tremendous output of scholarship has been enabled in no small part because Renaissance contemporaries championed archiving African American history, from the advocacy of Carter G. Woodson to the pioneering librarianship of Dorothy Porter Wesley.

James Weldon Johnson

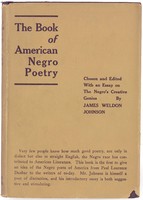

James Weldon Johnson’s first books included The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922, revised 1931), The Book of American Negro Spirituals (1925) and The Second Book of Negro Spirituals (1926). All are represented here. The poetry anthology confirms how much “good poetry, not only in dialect but also in straight English, the Negro race has contributed to American literature.” The Table of Contents pages present the then-contemporary poets Johnson included in 1931. The first book of spirituals clarifies how “the American Negro went a step beyond his original African music” by developing a “true chorus” in the response of call-and-response compositions. One example: “Steal Away.” The second book of spirituals presents 61 additional songs including “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child” and “Walk Together Children.” The musical arrangements in both books of spirituals were completed by Johnson’s brother, J. Rosamond Johnson.

-Robert Stepto, Professor Emeritus of African American Studies

Capturing the Folk: Zora Neale Hurston and Sterling Brown

Though the period of the Harlem Renaissance was characterized by the widespread urbanization of the African American population—the “Great Migration” of African Americans to Northern cities, as well as to urban centers in the South—many African American writers of the period drew their themes from Southern folk life. Two writers most noted for studying and incorporating folk culture into their work were Zora Neale Hurston and Sterling A. Brown. Hurston trained in anthropology with Columbia professor Franz Boas, the father of modern American anthropology. Her ethnographic research took her not only to her native Florida, but also throughout the South and the West Indies. She was also ever willing to turn her ethnographic eye on her own backyard, writing the glossary “Harlem Slanguage” to accompany her story “Book of Harlem.”

Though he had no formal ethnographic training (he received a master’s degree in English from Harvard), Sterling Brown took the opportunity of his first teaching position at Virginia Seminary to gather stories from the Virginia countryside, finding the inspiration for his poems about Slim Greer, “Big Boy” Davis, Stagolee, John Henry, and others. After James Weldon Johnson wrote the introduction to Brown’s first collection of poems, Southern Road, Brown wrote to Johnson insisting that the folk themselves, and not traditional folk ballads, were the source of his poems.

Langston Hughes’s Collection of House Rent Party Cards

The social and economic life of working class Harlem coalesces in these cards, collected by Langston Hughes. As the mass migration of southern African Americans to northern cities like New York peaked in the 1920s, new residents were crowded into small tenement apartments and charged exploitatively high rents, sometimes as much as double or triple what white counterparts might pay. Enterprising residents would organize house rent parties to cover their expenses. They provided the space and the live music—a piano player or even a three-piece band—and for between ten and fifty cents, guests could party all night long, while the hosts raised enough money to make ends meet. Prohibition-era home-distilled liquors and buffet spreads of home-cooked foods brought in additional revenue.

Hosts could print up cards advertising their “Social Whist Parties” at any number of local cheap printers, including the Wayside Printer, a man who wheeled a printing press down the streets of Harlem. Amused by the playful rhyming slogans and doggerel that appeared on most cards, Hughes began collecting them, amassing dozens of examples.

W. C. Handy and The Blues

Though he willingly adopted the moniker “Father of the Blues,” William Christopher Handy could be more accurately credited with finding the blues in the Mississippi Delta and exposing a much broader audience to the form. Born to formerly enslaved parents in Florence, Alabama, in 1873, Handy moved at 30 with his young family to Clarksdale, Mississippi, the heart of the Delta, where he began to learn the blues by traveling the countryside and observing itinerant performers. In 1912, he published Memphis Blues, a ragtime piano composition that included blues elements. Believing he had been cheated out of his copyright—he’d sold it to the publisher for $50—Handy founded Pace and Handy Music Company with lyricist Harry Pace. In 1914, their St. Louis Blues became Handy’s greatest hit. When Harry Pace left the company, it was rechristened Handy Brothers Music Company.

In 1926, Handy published a collection of blues arrangements titled Blues: An Anthology, with illustrations by Miguel Covarrubias. That same year, he invited Langston Hughes, who had just published The Weary Blues, to collaborate.

Anthologies

After the publication of The New Negro in 1925, two of the most remarkable anthologies of the New Negro era were Charles S. Johnson’s Ebony and Topaz (1927) and Nancy Cunard’s Negro Anthology (1934). Johnson assembled a group of young writers (including Jessie Fauset, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Countée Cullen) and allowed them to explore controversial subjects. Possibly most controversial was the art created by Aaron Douglas, Charles Cullen, and Richard Bruce Nugent. Cullen’s cover, for example, presents sexually ambiguous and sexually involved black and white nude figures. Nugent completed four Drawings for Mulattoes; drawings two and three appear here. As scholar Caroline Goeser observes, “Nugent illustrated an interstitial racial type, aiming to destabilize conventional definitions of racial and gendered identities.” Nancy Cunard notes the racial strife of her time (“The Scottsboro frame-up…Forty-eight lynchings in 1933”) and proudly cites that her book assembles “150 voices of both races.” The poetry section, for example, includes Negro Poets, West Indian Poets, and White Poets on Negro Themes (including herself). The Cunard anthology is distinctly “Black Atlantic” in its contents. While the first section is titled “America,” the final sections are “West Indies and South America,” “Europe,” and “Africa.”

-Robert Stepto, Professor Emeritus of African American Studies

Carter Woodson and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History

Known as “The Father of African American History,” Carter G. Woodson founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915 to promote African American history as more than just the history of slavery. He began publishing The Journal of Negro History the following year, today known as The Journal of African American History and still the leading scholarly publication on the topic. Woodson promoted the teaching of African American history in elementary and secondary schools, particularly to African American youth. The child of two former slaves, Woodson earned a B.A. from University of Chicago and a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1912, making him only the second African American (after W. E. B. Du Bois) to earn a doctorate in Cambridge. He would go on to publish some fifteen books, including monographs, textbooks, and edited collections of source materials. Woodson’s view of African American history was of a piece with James Weldon Johnson’s notion of the influence of African American literature. He believed that educating people would change their attitudes. His view of African American history was capacious—this calendar of Negro History includes the birth of “open-minded poet” Walt Whitman.

In February 1926, Woodson announced the creation of Negro History Week, a week of celebration anchored around the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Undoubtedly his most lasting legacy, the week evolved into Black History Month in the 1970s. Woodson was awarded the N.A.A.C.P.’s Spingarn Medal, an award for the highest achievement of any African American, in 1926.

Collecting and Preserving the African American Past and Present

It should not be viewed as a coincidence that the world’s greatest library collections of African American letters and history—the Moorland Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in the New York Public Library, and the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts and Letters at Yale University—were all founded around the Harlem Renaissance period. The study and celebration of African American life and history was very much a part of the era’s ethos, and black bibliophiles like Jesse Moorland, Arthur Spingarn, and Arthur Schomburg were ready to contribute. Moorland donated 3,000 volumes to Howard University in 1914; Schomburg’s 5,000 books and 3,000 manuscripts were purchased by the New York Public Library with the help of the Carnegie Foundation in 1926 and housed at the 135th Street Branch Library, renamed for Schomburg after his death in 1938.

Upon receipt of Moorland’s donation, Professor Alain Locke composed a prospectus for the Howard Library, calling for a Curator of Negro-Americana with funds to augment the collection. In 1930, Howard hired librarian Dorothy Porter Wesley, who stewarded the collection for more than four decades. Along the way, Porter revolutionized the library field to increase inclusion of African American materials, expanding the Dewey Decimal classification system to accommodate works concerning African Americans beyond sociology.

The James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Negro Arts and Letters, founded by Carl Van Vechten, 1941

After James Weldon Johnson died in a car accident in June 1938, Carl Van Vechten formed a committee to memorialize Johnson that included Theodore and Eleanor Roosevelt. Though plans were made for a statue at the 110th Street entrance to Central Park, with Richmond Barthé awarded the commission, the advent of the Second World War ultimately foreclosed this idea.

Meanwhile, Carl Van Vechten had been looking for a home for his collection of African American books, photographs, and letters. Choosing Yale University and naming the collection in Johnson’s honor in 1941, Van Vechten set to soliciting donations from others. He enlisted the help of Dorothy Peterson and Harold Jackman and published articles inviting donations in The Crisis and Opportunity. By the time the collection formally opened in 1950, more than 150 people had made in-kind donations, and several had also contributed to an acquisitions fund. Expecting Yale librarians to be ignorant of African American culture, Van Vechten included editorial notes and biographies in the 650-page catalog of the collection.

Everywhere and Nowhere: Harlem in the Popular Imagination

Though some historians object to the phrase “Harlem Renaissance,” preferring “New Negro Renaissance” or “New Negro Movement,” the events of 1917-1939 undoubtedly put Harlem on the map, making the neighborhood inextricable from African American culture. It was playing on this association that in 1948 Ralph Ellison wrote the essay “Harlem is Nowhere,” an attempt to disabuse Americans of their romance of the neighborhood, writing, “This is a world in which the major energy of the imagination goes not into creating works of art but into overcoming the frustrations of social discrimination.” Ellison’s essay went on to focus on the LaFarge Psychiatric Clinic and was meant to accompany a portfolio of photographs by Gordon Parks, but the essay was shelved until 1964. In 2016, the Art Institute of Chicago reunited Ellison’s essay and Parks’s photographs in an exhibition.

In the near century since “the Negro was in vogue,” artists and critics have constantly attempted to define, redefine, and preserve the meaning of Harlem. In 1969, the Metropolitan Museum of Art held an exhibition titled “Harlem on My Mind, Cultural Capital of Black America 1900-1968.” The exhibition was very poorly received, criticized in part for being largely documentary and sociological in nature, and excluding paintings and sculpture by African American artists. At the same time, the exhibition revived the reputation and career of James Van Der Zee, then living in poverty. The year 1972 saw the publication of two major works of history: Nathan Huggins’s Harlem Renaissance and The Harlem Renaissance Remembered, edited by Arna Bontemps. These books were followed by dozens more, making this among the most studied chapters of American history.